The secret life of my magic crystal singing bowl

The Egyptian Blue Alchemy Bowl

Amongst the dozens of instruments that I use in sound meditation and healing, there’s one in particular that engages my mind, body, and spirit equally. I am a recovering academic since discovering that I can physically experience sound in my body, and that has led me to a more intuitive sound practice. Listening with my body and not just my ears and mind has opened up new and exciting experiences for me that were not taught in graduate school! This blog is about the meeting of experience and intellect. it is about my magical Egyptian blue alchemy crystal singing bowl and modulated to help sound bath practitioners, sound healers, and those interested in hearing more deeply into their instruments. And so, I’d like to take you on the journey of discovery that I’ve travelled to unlock some of its secrets.

Listen first!

First, before telling you anything about it, I’d love for you to experience it (oops…i’ve already failed since I told you it is magical!). I encourage everyone I teach to experience something first before trying to understand it. In Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Persig says “Reality is always the moment of vision before the intellectualization takes place. There is no other reality.” In other words, once we start thinking about something, we are no longer in the experience of it. If you are interested in some science behind this notion from one of the 20th century’s greatest philosophical fictions, I recommend reading The User Illusion by Tor Nørretranders. Experiencing something takes us much deeper and is more multi-faceted than intellectualization (past experience) or expectation (anticipated experience). Rather than listening FOR things in sound, which is what you would be doing if I described it to you first, I encourage you listen TO these recordings and just observe and note what you hear and experience. Play each version a few times and listen with your ears, your emotions, your whole body and your spirit. There’s plenty of time for the mind to get involved later! And don’t be concerned that you what you experience may be different from what I experience. The beauty of these rich instruments is that we will all perceive them in our own way.

What did you experience and hear? What did you feel How much detail did you notice? Are there aspects below the surface that inspire you to go deeper? If so, read on!

The process of analyzing sound is one of educating my attention. Not for the purposes of narrowing it (as did the ear-training of my 12 years of higher education), but rather for expanding it so that I can perceive more aspects and possibilities with each new sound or instrument I encounter. I analyzed this bowl extensively because of how I first experienced it. I purchased it from Crystal Tones because originally it was sold as a bowl that connected ancient Egyptian energies with modern technology through the element of vanadium (although, it appears they have now changed the “alchemy” of this bowl). Since I use electronics in my sessions, my intention with it was to harmonize the intellectual, technological and magical, mysterious, and intuitive realms into every session. Intellect and intuition are highly compatible to me. They are two different ways of experiencing. One without the other becomes a limiting factor in my practice, and my goal is to practice maximal expansion instead of restricting my understanding and potential. Analysis helped me explain some things about this bowl’s voice, while others remain deeply mysterious to me! A deeper spectral understanding opens up a kind of alchemical listening that I invite you to engage in.

What I feel and hear

Personally I feel the vibration of this bowl from my shoulders up through my head. It is a pretty “tight” and focused vibration, which jives with the alchemy of the bowl, and also what I hear with this bowl. There are two things I experienced when I first played this bowl that have confounded my 40 years of understanding of how sound works. Maybe you experienced them also.

First, when I strike the bowl, the sound slowly moves between my right and left ear. We are stereo creatures, but to have a single point source of audio activate both ears differently over time is not something I have experienced elsewhere except in electronic compositions where the sound has been intentionally mixed by the composer across the stereo field. Other sounds, like a stream or wind move across the stereo field as well, but usually in one direction, and they are not single point sources. I have experienced the bowl in many varying rooms and it acts the same no matter what size the room. It also works if I turn my head slightly off-axis (i.e. with my nose pointed away from the bowl). Somehow it is creating binaural beats without headphones! This low frequency oscillation is a main feature of many bowls (more on that below), and I’ve noticed it to varying degrees in other crystal bowls, but to lesser degrees. With some bowls it feels more like a moving intensity, like i’m feeling the compression and rarefaction densities of the air molecules in my brain, rather than hearing an acoustical movement across the panning field. I also notice that it may be a proximity effect, as the further away I get from the bowl, the less noticeable the acoustic effect. This bowl has definitely expanded my acoustic, somatic, and psychoacoustic listening skills, deepening my practice significantly.

Second, I noticed that when I sing perfectly in tune with the bowl (i.e. there is no beating caused by two notes at slightly different pitch, like how a violinist or cellist tunes each string on their instrument against another string), and then stop singing, the singing note I heard in my head all of sudden would sound a half step lower than the bowl. Adding my voice back again, the two would sound the same and in tune to my mind. So, when acoustically in tune, this bowl would reveal a psychoacoustic (perceptual) difference in my mind, which still mystifies me to this day. I started experimenting with it and noticed that with practice, I could pitch bend my mind’s note to match the bowl’s note, but it took time and practice. My hypothesis is that my perception can literally be “out of tune.” An interesting research question that I’m still trying to experimentally wrap my head around is: can I demonstrate that our inner perception of pitch can get out of tune, and if so, can we learn how to tune it? Is this what is happening with people that are tone deaf, or can’t carry a tune? Could it be that when we misunderstand others, it is because our perception of them, and what they are saying is out of tune? Can we develop a practice that helps us communicate more clearly by tuning our perception to accurately hear what is being communicated? This experience has led me to plumbing a greater depth of what tuning means and that it is not just an acoustic practice, but also a psychoacoustic one as well.

Using tools at my disposal, I looked into the software analysis of the bowl to see if there were any secrets that could be teased out. The spectrum of a sound is shown through a sonogram, which reveals all the frequencies present and their amplitudes (relative loudness). The composite spectrum of a sound is its physical characteristics measured precisely, and that spectrum is what creates the sound’s timbre, which is our perceptual or descriptive description of it.

Sonogram Analysis

There are many factors that impact the spectrum (timbre) of the two sounds that I am analyzing. The type of beater (in this case a leather wrapped pvc pipe), how hard the bowl was struck, and where it was struck, are aspects that can affect the timbre, and thus, the spectrum of a singing bowl. Bowing technique can alter the timbre and behavior of the spectrum over time as well. How much pressure and clarity it was bowed with can change the frequency components from one occurrence to the next (measured in cycles per second, or Hertz, abbreviated Hz). Therefore, my analysis is not exhaustive of all possible spectra that this bowl can produce. What I’m analyzing are single occurrences of the bowl being struck and bowed. Can this analysis shed light on some of the mystery that I experience with this bowl?

The graphs below are made in iZotope software, but anyone can see these kinds of graphs in the free program Audacity. There is quite a bit of information to assimilate here. But to start with, I encourage you to look at the graph, and again, listen to the sound a few times to see if you can intuitively correlate visual information with what you are hearing. I have included the sound file again so you can easily watch while you listen.

Listen again!

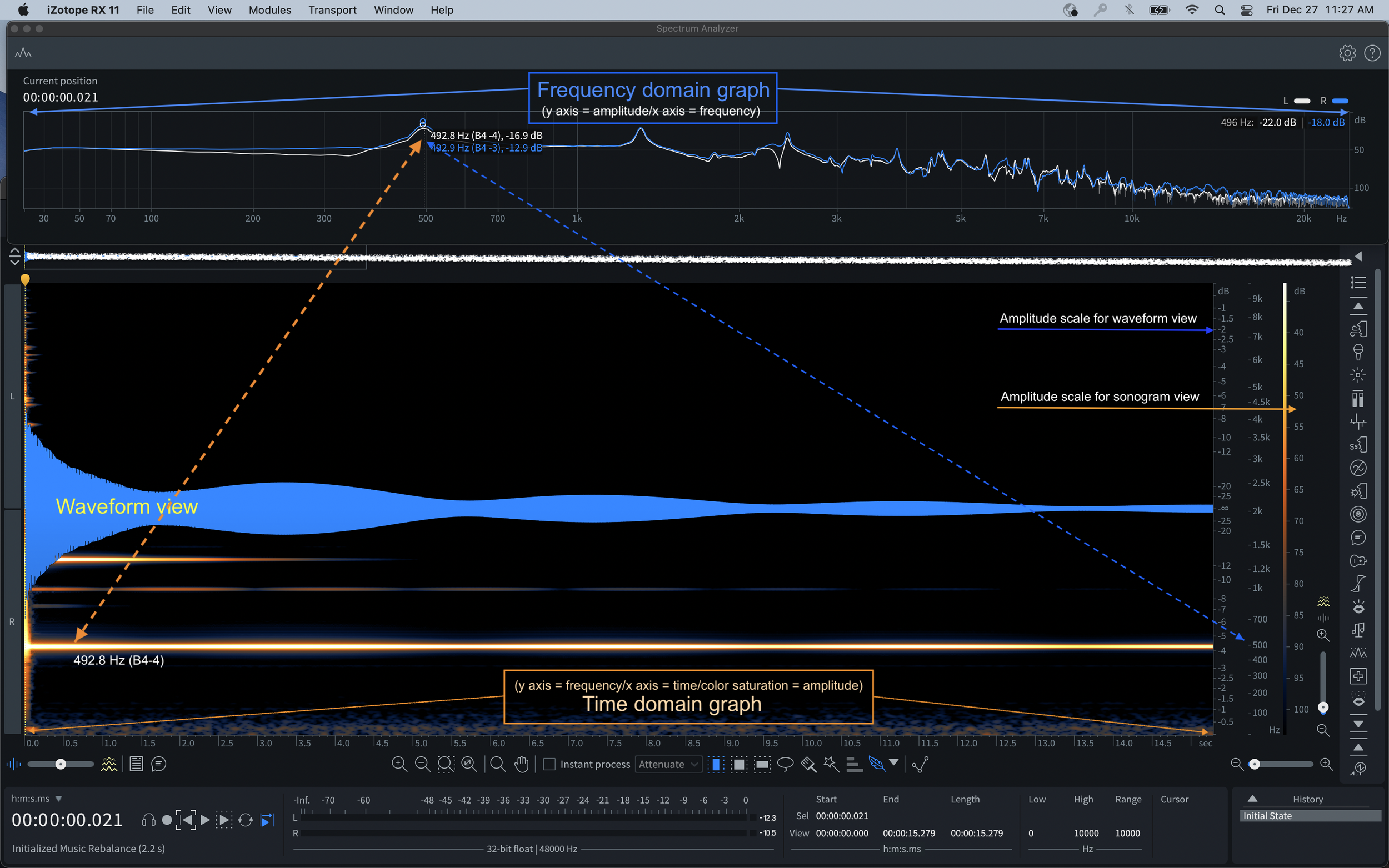

iZotope software analysis of first 15 seconds of the struck bowl (close mic’ed in stereo with paired Shure KSM 141: 48 kHz, 32 bit)

Sonogram description

There are three different graphs in one here which I will describe so you understand what you are looking at, and then I’ll describe the features of the sound it illuminates.

First, at the top (separated by the fuzzy white line), is the “frequency domain” view. It shows the frequency components at a single point in time where the cursor is located (in this case, at the very beginning of the sound file). The y axis is amplitude (loudness) and the x axis shows the frequencies present at the cursor is location. You can see the “fundamental” tone is B4-4 with a frequency of 492.8 Hz (with very slight variation between left and right channel).

Frequency Domain Graph (at the time of the attack)

The lower part of the graph contains two superimposed views in the “time domain.”

Time Domain Graph

“Waveform view” is the blue shape in the center which shows the overall loudness profile over the entire 15 seconds of sound. Zooming in allows us to also see the wave shape, but we won’t be looking at that here. The second time domain view are the lines of varying shades of orange and yellow. These are the exact frequency components present. The lighter the color, the louder the frequency, and their combination with relative amplitudes, is what makes the unique timbre and behavior of this particular bowl.

Let’s zoom in a bit to get more clarity on some individual components of this bowl’s sound.

Amplitude profile

The amplitude profile (also sometimes called the impulse) is the evolution of a sound that we perceive as its behavior over time. Generally, every sound has a unique unfolding in four stages: attack, initial decay, sustain, and release. This ADSR envelope is also an aspect of the sound that helps distinguish its unique timbre and behavior. If you think about a struck crystal bowl, the attack is pretty rapid with a firm/hard beater. We can easily see that initial burst of energy in the waveform view. The following decay is often hard to hear without practice, but after the excitation, there is usually a relatively quick drop in amplitude once the excitation energy has ceased, which again, is clearly visible in the waveform view. Then, after that initial decay, the sustain portion rings a length of time determined by how hard the bowl was struck, the type of beater, and the quality of materials and process used to make it. The acoustical space it is in will also affect the length of ring, and based on experience, the energy of the room and practitioner affects it as well (but that is a topic for another blog). Finally, there is no release naturally for a singing bowl unless it is dampened by the performer since the laws of physics (the second law of thermodynamics?) are in affect as the input energy dissipates. A release can be created and its length and characteristics will be determined by how it is dampened. Putting your hand firmly on it will release it quickly. Throwing a towel on it will release it more slowly. These ADSR stages of the amplitude profile determine the loudness shape of the sound over time, which also affects the timbre. We could say it is like the skin of a human that reveals the shape of their body. But let’s go more than skin deep!

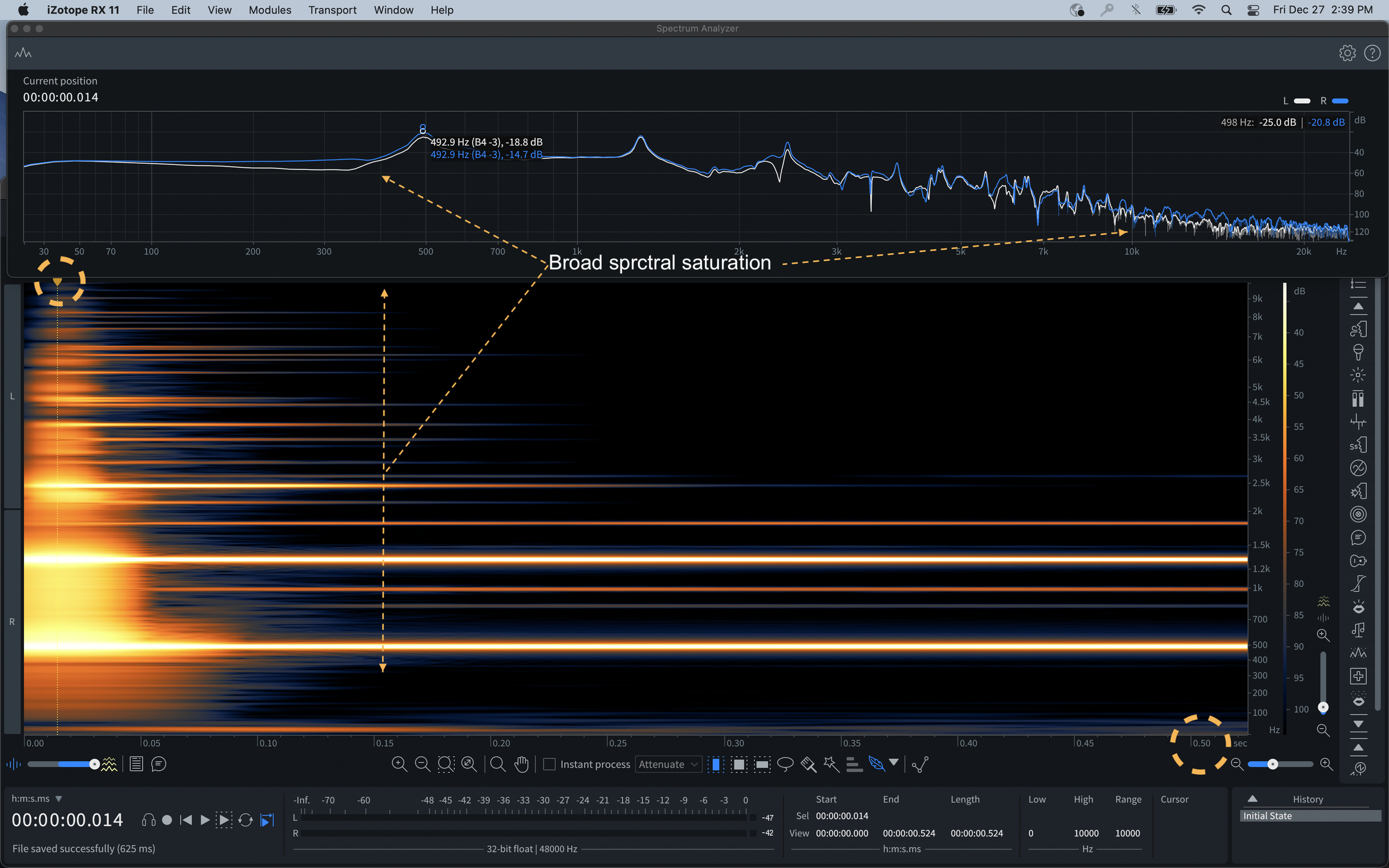

Below is the attack portion of the struck bowl. The following graph is a view of the first .5 seconds, and even though we can see some discrete pitches, the sonogram reveals a broad spectrum of frequencies. This “messy” attack is common in instruments, and is called an attack transient because the spectrum has many rapidly changing components excited by the method of initiation (strike, breath, bow, etc.). It is often relatively noisy. Take a flute note for example. The attack transient of every flute note is noise caused by air (wind/breath) across the blow hole. There is no way to eliminate this feature, and in fact, that noise impulse is what makes the flute sound like a flute. However brief, it is the most defining feature of the instrument! As you can see, the noisy attack of this bowl settles down rather quickly, within .1 seconds of the strike. And from there the partials of the bowl ring more clearly. The “production noise” is an important part of the sound profile of any instrument, and is something I play with a lot. To me it is a sonic marker of the human presence activating the instrument. Think key clicks on a saxophone or tuba, or the squeak of guitar strings as the player’s hand moves between chords. I often exaggerate it as a separate instrument. One example is using my hand on the edge of a bowl to created a pitched noise sound, like wind. And in the bowed version, you can hear the felt on the bowl before the notes begin to ring out. Learning to hear these discrete and subtle components of a sound is part of the sound healer’s practice with whatever instruments we play. This practice will dramatically expand the sound library from instruments you already have in your orchestra!

Egyptian Blue Alchemy bowl first .5 second attack transient (the frequency domain graph shows the spectrum at the time where the circled curser was located at .01 seconds)

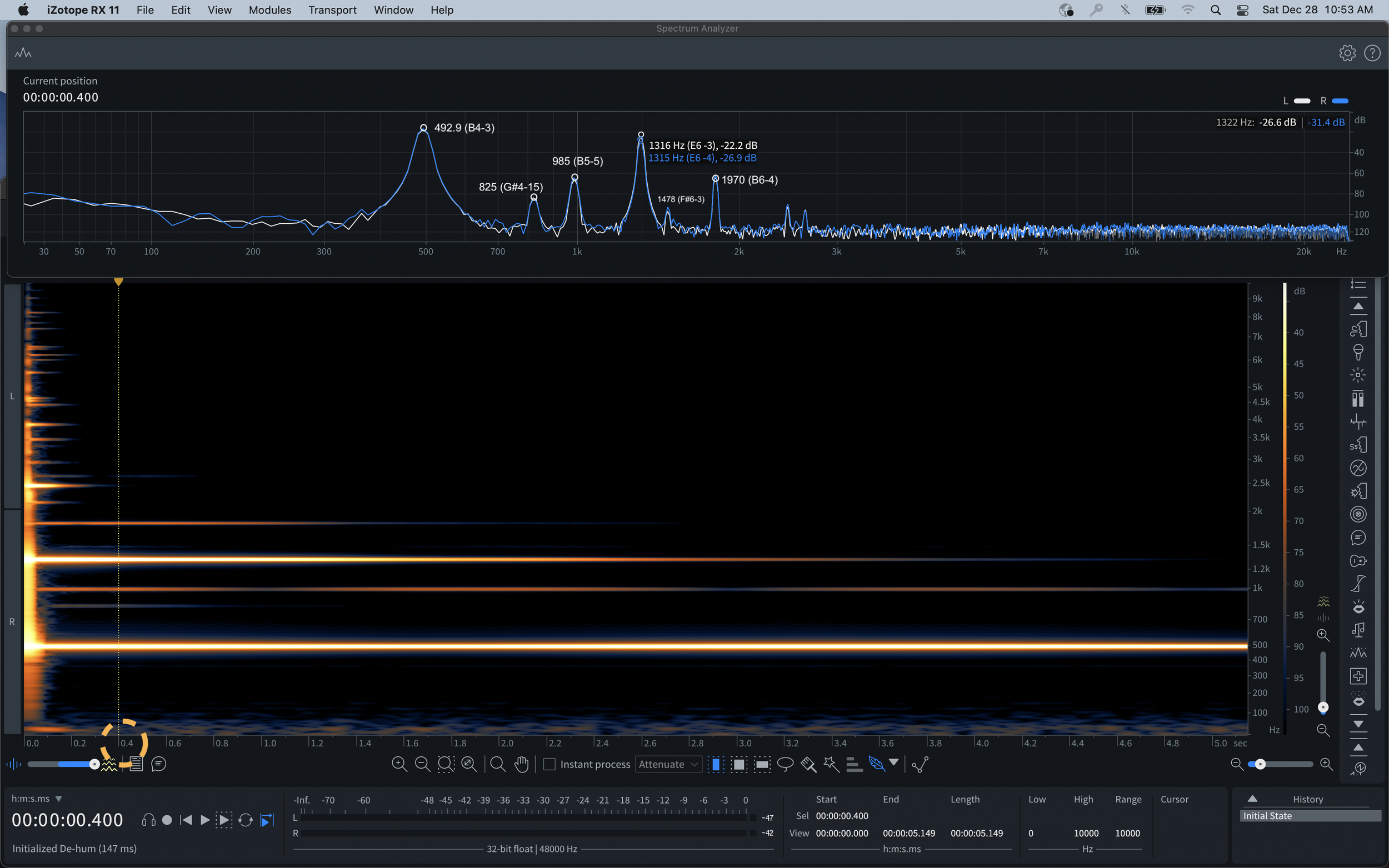

At .3 seconds after the attack, the sonogram reveals that the bowl has settled into its clear fundamental and harmonics, two of which are much stronger than the others. The peaks in the frequency domain graph below, correspond with the colored bands in the time domain graph.

Up to this point, there are no surprises in the sonogram, but here’s where it gets interesting! If we look at the notes of the steady state (sustain) portion of the bowl, there are some unusual things. Below I’ve labeled and numbered the prominent notes and frequencies.

The total frequency content, and their relative loudness, or amplitude, is what makes up the spectrum of this bowl. The software labels them with frequencies for precision of mixing and editing in software, but as humans, we perceive in terms of notes which are always in relationship to each other, within a specific tuning system. In this case, the software is using A 440 as the tuning reference. Most of us hear and think of notes in music and not frequencies. Frequencies are unique spectral measurements, while note names are relative to a tuning system. 432 is a different frequency than 440, but they are both called “A” in two different tuning systems. Working with frequencies is helpful when trying to figure out the ratios between notes present in a spectrum. Unless you are practicing clinical research on the affects of specific frequencies, or mastering complex music mixes at a mixing board, then thinking musically in terms of notes is probably more helpful. And it’s in the ratios between notes where the sonogram of this bowl shows some interesting, even duplicitous relationships.

The fundamental frequency of B4 (1) is the main note that we perceive because it is the loudest partial. Most sounds are made up of a set of multiple partials. Partials are fequency components that are present in addition to the fundamental, because any vibrating body produces sub-vibrations at multiple proportions to the whole. I’ve labeled five additional partials present in this bowl’s sound. Partials are also sometimes called overtones (which are counted above the fundamental). Relationships between partials can be harmonic, in whole number ratios to each other, or inharmonic based on fractional ratios. (See Wikipedia’s article on harmonics in music for a discussion of terminology).

We can see above that partial 3 is in harmonic relationship with the fundamental (1) because their ratio is 1 : 2, or one octave (985/492.9). Partial 6 is also in harmonic relationship with the fundamental because they are in 1 : 4 ratio, or two octaves (1970/492.9).

Partial (4) is in an inharmonic relationship with partial (1). Partial 4 (E6) has an amplitude nearly as strong as the fundamental, and it is easy to hear both live and in recording (and depending on where the bowl is struck, this partial can be louder than the fundamental). The ratio between them is 1 : 2.67 (1316/492.9). The very weak F#6 (5) would be a 1:3 ratio with the B5, but its low amplitude makes it imperceivable, especially next to the very prominent E6. Instead of a harmonic B to F#, this bowl has an inharmonic B to E in its series of partials. B to E in musical terms is a dominant (V) to tonic (I) relationship, suggesting E, not B as the tonality. The B fundamental could be the 3rd partial if E (329 Hz) were the fundamental (1 : 3 ratio), but that is not the case. So it is as if there were a ghost (implied) fundamental E, below the B. The G# (partial 2) is also inharmonic in relation to the fundamental B at a ratio of 1 : 1.67, but could be a harmonic of a fundamental E. Is your head spinning yet? That’s what this bowl does!

What is unusual is not its inharmonic spectrum, but rather that the relationship between partials have the foundation of two different harmonic series for our brain to sort out. These harmonic/inharmonic relationships cause the duplicitous quality of the bowl that I mentioned above, and perhaps this is where its magic lies. Could it also explain why my perception feels out of tune with it sometimes? I’m not sure, but I do know there are subtitles in this bowl that make it quite slippery and agile in terms of its musical function in a session.

Inharmonic partials that are slightly out of tune with each other are what creates low frequency oscillations which are a powerful device to help a client reach the Theta brainwave state in a session (4-8Hz). You can read about that in a previous blog Sound Healing through Transduction. So let’s see what this bowl has to offer in LFOs!

The LFO Experience

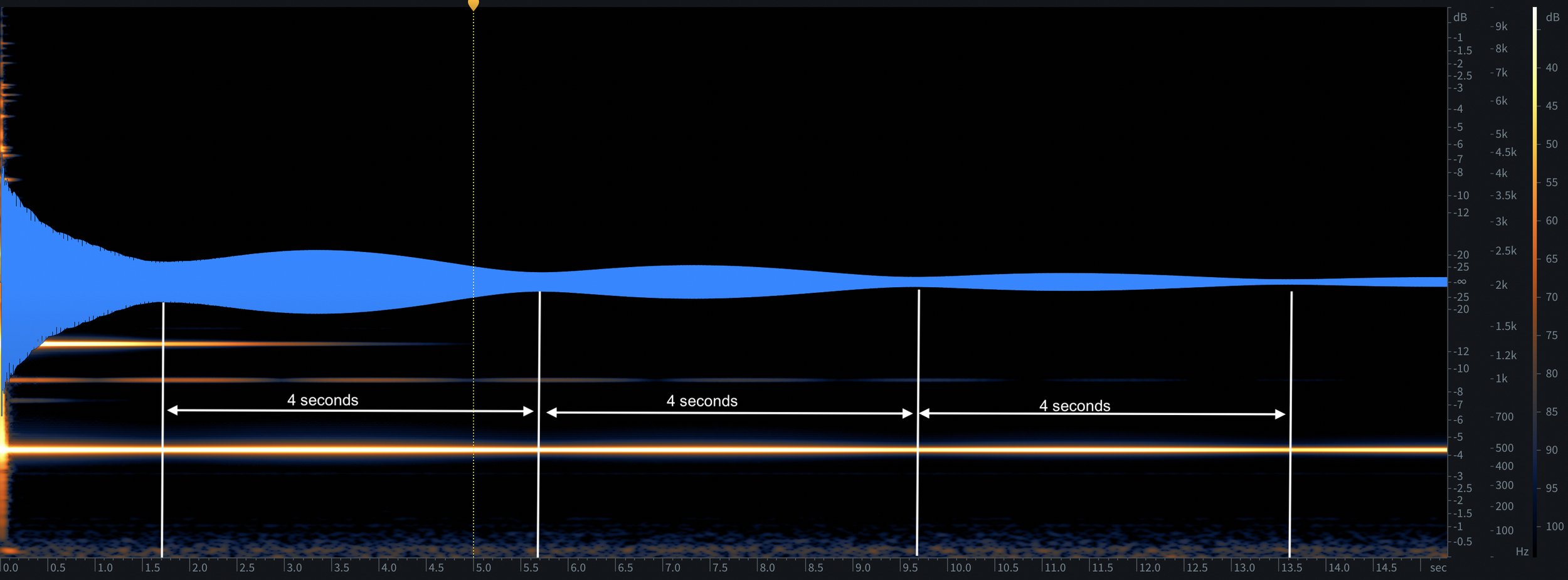

Almost every single metal bowl I’ve heard has an inharmonic spectrum which is the source of their potent low frequency oscillations. And as shown, this crystal bowl does too. In the struck version, there is a low frequency oscillation that occurs approximately every four seconds (.25 Hz), visible in the mono sum of the waveform view.

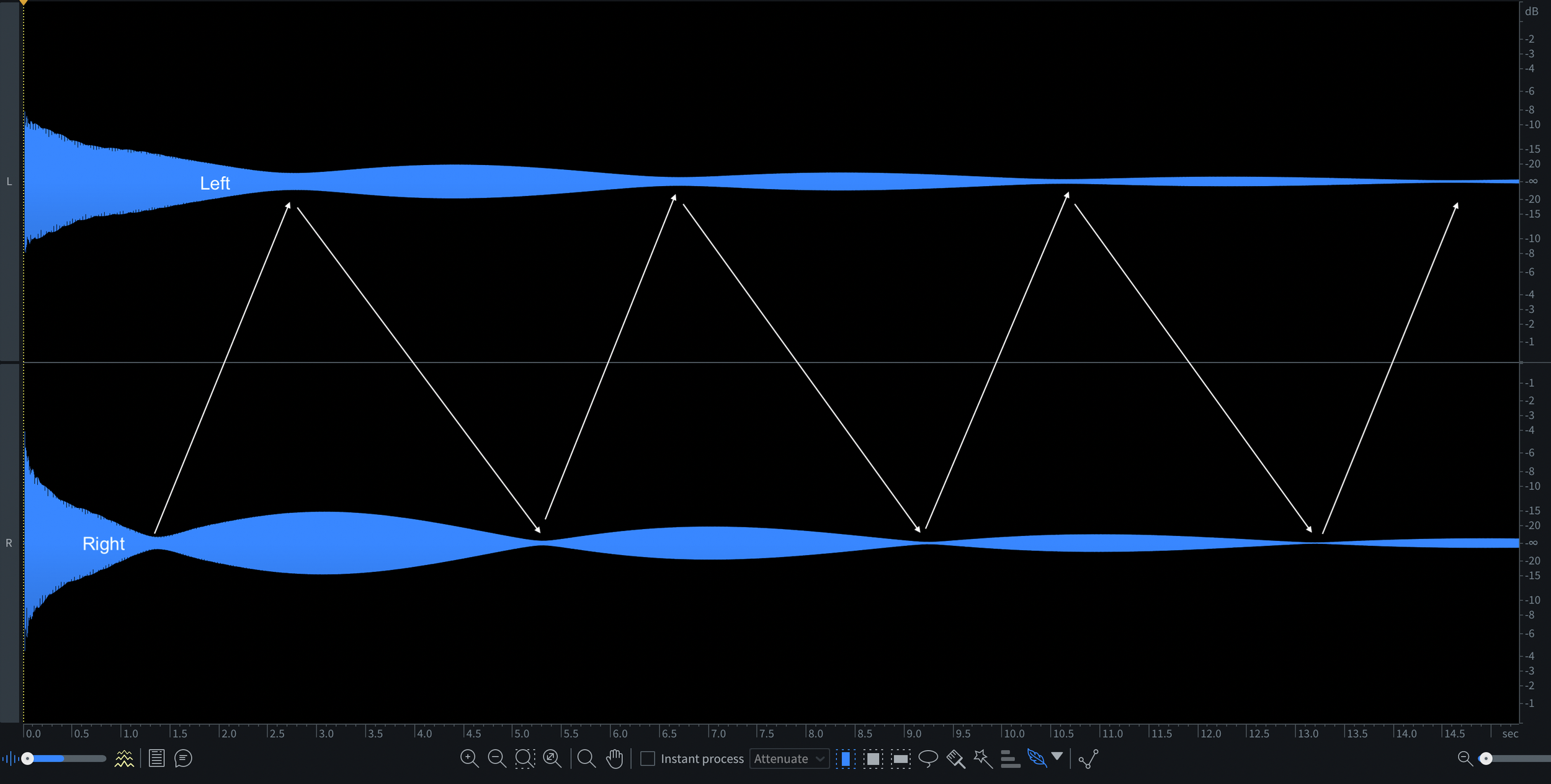

Viewing the stereo channels separately reveals that this low frequency oscillation is offset (out of phase by about 100°) between the left to right channels. The microphones picked up the panning that I hear confirming that it is an acoustical phenomenon (physically present in the sound of the bowl), and not psychoacoustic, or just happening in my mind.

Low frequency oscillations occur when partials destructively interfere with each other, cancelling each other out and periodically dampening the amplitude profile. When this bowl is bowed, a different low frequency oscillation occurs approximately every .8 seconds (1.25 Hz).

There is no attack transient on the bowed version because of the slow attack (not shown on this graph). You can see the low frequency oscillation on both the waveform view, and the sonogram view in this example. Also notice that some of the higher partials have different low frequency oscillations than the fundamental B. Some metal bowls have 3 or 4 LFO’s happening simultaneously. This graph also shows where I stop bowing and the sustain portion of the sound changes to the 4 second LFO discussed above. One might be tempted to equate the rate of the LFO with the speed of bowing, but that is not the case. The rate of the LFO is determined by the physics, material, and shape of the bowl.

One final thing to note is that the upper harmonics remain audible during the bowed segment, but stop once the bowing stops except for the E partial which rings for 5 or so seconds after the bowing stops. The bowing acts as a continuous excitation, but less intense and without the transient effect (noise) of striking the bowl.

Notice that in this instance the harmonic F#6 partial is slightly louder than the inharmonic E6 partial. I chose to locate the cursor here because it shows the weakest fundamental amplitude and some of the strongest upper partials. Also present is the 5th harmonic (D#7-18) and 7th harmonic (A7-35), which naturally occurs in an instrument that resonates with a harmonic spectrum. The “out of tune-ness” of both these partials are normal for harmonic spectra, because the note names we assign to them are relative to equal tempered tuning at a tuning standard of A440. The names of notes in our equal tempered tuning system, which does not occur in nature, is at odds with the physics of naturally vibrating bodies. The changes in the saturation of line color in the spectrum view reveals what I call the behavior of the sound. In this case, shifting relative amplitudes between partials and the low frequency oscillations.

The differences in the struck and bowed versions of the bowl do not reveal radically different frequency data. What is clear to see is that some aspects of the bowl are accentuated by each method of playing, and thus can serve differing purposes in performance or sound healing session, and how I use it with other instruments.

Conclusions

Understanding this bowl through spectral analysis takes nothing away from my experience of it. In fact, it amplifies how I use this bowl and for what purpose. Knowing that it has two tonalities helps me determine what other bowls to play with it and when. Understanding the difference in LFO rates between struck and bowed can help me bring a specific affect into the session especially in combination with other bowls or instruments. When I work with clients, this research is never in the forefront of my mind, but the understanding it brings helps me access another layer of wisdom in making sound for them.

I do the analysis part because I am curious, and I like to understand my unusual experiences at as deep a level as possible. This kind of analysis also helps me hear more deeply, not just with this instrument, but with all instruments. It helps me see what I am bracketing out of my listening experience either through ignorance, in-attentional deafness, or simple complacency and not listening with care. It teaches me new ways to educate my attention, and deepen my awareness of all sound. My potential to impact others in more subtle and deeper ways is extended by listening intelligently to any acoustical situation, and to the energy in the room. When things are in tune, the resonance of everything being played, and the people receiving it, increases, and an ease joins the proceedings. This is a difficult thing to measure or verify, but I’m guessing if you have read this far, you know what I’m referring to.

As a practitioner, I have to be very cautious against hearing what I want to hear, instead of what is actually in the room. Deep analysis also helps me harmonize the outer acoustic world with my inner perceptual and psychoacoustic impressions. Seeing is a sense of the will (we see what we believe, and not the other way around). Hearing is a truer representation of the physical world around us. It is a quick sense that helps us “see” behind us, informs us on what kind of a space we are in, what else is in that space, and where it is located. In sound healing, it is the primary sensual relationship with our clients, and a reflection of the resonance within and between each of us.

Understanding how this bowl is tuned, helps me understand my own tuning. As humans, we are all in a constant state of de- and re-tuning, whether by choice through intentional awareness, or by being subject to forces without our awareness or consent. I am a more conscious self-tuner, with greater ability to create a field of potential for others to tune, when my intuition is informed by intelligent understanding. I am able to use my tools more wisely instead of being used by them in a life-long pursuit of building the biggest, most rich box of sound tools possible. I hope this analysis shows you some tools to help with deeper understanding of what you do, and how you do it. Happy oscillations, and tune well!

Some additional links:

Visit my web site for more information on commissioning personalized sound, my sound-practice, or my compositions, and for Harmony Farm Sacred Space and Sound.

Dr. Paul Rudy is a life-long teacher and leaner. He is an award-winning composer, sound artist, sound practitioner, photographer and land artist. He is Curators’ Distinguished Professor of Music Composition, specializing in electroacoustic composition, at the UMKC Conservatory since 1998, where he is currently studying the impact of sound on speech communication in the operating room with Surgilab (UMKC Medical School) supported by the National Institutes of Health. His youtube channel @innersoundworlds contains healing mantra music, and his music and CD series 2012 Stories can be found online.